Tefalhead is not an angry man, in fact, Tefalhead is a mild-mannered medical writer who nonchantly keeps on plodding on in his own Tefalhead world; indifferent to most happenings in the world. But, that all changed last week when he saw headlines like the one below:

Tefalhead was not the only one to be stirred by the release of the PACE(Pacing, Activity, and Cognitive behavioural therapy, a randomised Evaluation) study of various treatments for myalgic encephalomyelitis (M.E)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) in the Lancet this week. The Twittersphere, and the internet as a whole was full of chatter spinning off in every direction following on from the PACE study publication, with blog titles such as “Invest in ME: PACE trials are .Yup, that’s right claims that a study published in the prestigious journal The Lancet’ are BOGUS! Controversy surrounding the study was not confined to random bloggers, tweeters, or such like but the M.E. Association had this cracking press release:

Yup, you read it correctly “Results are at serious variance to patient evidence…“. Let me get this right, one of the main M.E/CFS patient advocacy groups in the UK disagree with the results published in the Lancet, one of the “world’s best known, oldest, and most respected general medical journals“ according to Wikipedia!

It’s now Sunday, and Tefalhead has recovered from the red mist that blinded his thoughts on Friday. Tefalhead is a scientist by training and although he desperately wanted to blog about this on Friday, he knew his scrawlings would lack objectivity. However, after two days of chillin’, his objectivity head is back on, but first, Tefalhead has one thing to disclose…nope, we’re not talking about receipt of consultancy fees from The Department of Health, or that Tefalhead is one of the co-authors’ of the study. No, this is much more personal. Tefalhead’s wife has M.E/CFS a condition that is misunderstood by all, massively impacts lives of those afflicted with this condition and has no known magic bullet in terms of a cure. In brief, this condition sucks BIG time- and to see the love of your life affected by it – well, there are no words for it. Needless to say, because of this fact, there will be inherent biases in what I repor. It’s inevitable folks- so treat what I say next, with CAUTION.

What did the study involve?

The study was carried out by researchers from several UK institutions, and was funded by the UK medical research council, The Department of Health for England, the Scottish Chief Scientist Office, and The Department of Work and Pensions. The study was published in The Lancet online this week at http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(11)60096-2/fulltext . Whoa, right, let’s backtrack for one second…. “funded by… The Department of Work and Pensions’? For non-UK readers, the Department of Work and Pensions is an UK government department that manages welfare and pension policy in the UK, including provision of financial support for people claiming disability benefits. So what on earth are these guys doing funding a clinical study to assess the effectiveness and safety of treatments for patients with M.E/CFS.? Hmmm… Tefalhead, asked the very same question. After digging around a bit, he stumbled across this document http://www.meactionuk.org.uk/magical-medicine.pdf from Malcolm Hooper, an Emeritus Professor Of Medicinal Chemistry…. This document seems to open up a whole lot of controversy surrounding the PACE study, including suggestions that the Department of Work and Pensions could use the data from the study to essentially remove many CFS patients from benefits system in the UK. That would save some money right? Not a bad thing in this era of austerity measures. Tefalhead does not want to distract from the main analyses reported in the Lancet study, but the fact that an external body that has inherent interests in the data reported actually funded the study… is a little bit fishy. However, it happens all the time with pharmaceutical companies for example, who are continually reporting the results from their clinical studies in manuscript articles. When reading such articles one needs to take into account the phenomenon of funding bias and acknowledge that the conclusions of a study could be biased towards the outcome the funding agency wants. To be clear, Tefalhead is not saying the funding bias has occurred in the PACE Lancet study, but we need to take this into account when considering the data.

So… where did this study come from?

Details of the Study Design are given in Box 1. In brief, 641 patients were given one of four treatments: specialist medical care (SMC)(provided by doctor with specialist expertise in CFS), SMC plus adapative pacing therapy (aims to assist CFS patients in optimally using their limited stores of energy); SMC plus cognitive behaviour theapy (CBT; believes that fear responses are linked to physiological response and make the fatigue worse and involves strategies such as establishing a healthy sleep patterm addressing fears, problem solves and working with a therapist to increase mental and physical activity), and SMC plus graded exercise therapy (GET; believes that fatigue can be reversed or reduced using gradual increases in activity and uses strategies to establish a baseline of acheivable exercise followed by negotiated incremental increases in the time spent being physically active).

Patients were given questionnaires to fill in to assess the effectiveness of treatment and were unmasked to treatment, ie it was obvious what treatment they were receiving. As a result, their own expectations of what treatment they were receiving, could have influenced the final results. To account for this, the investigators did assess patient expectations before treatment started. The study clinicians also used questionnaires and scoring methods to assess the impact of treatment on the patients’ overall health, Any adverse events were also monitored forthroughout the study (any adverse change in health or side effect during treatment).

There were no biological measures assessed during the study, which would have been expected for a condition such as CFS where the biological basis of the condition is unknown. Tefalhead thinks this is a big shame given the large amount of patients involved in the study.

What did the researchers find?

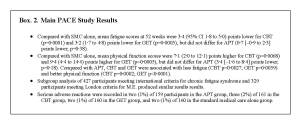

After 1 year, the study found that fatigue was significantly lower for CBT and GET compared with SMC alone (See Box 2). However, there was no significant difference between APT and SMC. Physical functioning (the ability to perform a range of activities from self care to more vigorous acitivities) was significantly higher for CBT and GET versus SMC, but there was no significant difference between APT and SMC. Compared with APT, CBT and GET were associated with less fatigue and better physical functioning. The Oxford criteria for diagnosi of ME/CFS are broader than other criteria used, and as a result, may cover a broader range of conditions that may be unexplained and thus categorized as ME/CFS. When different diagnostic criteria for CFS were applied (the international CFS criteria and the London criteria for ME), two-thirds of patients met the international CFS criteria and about half met the M.E criteria, which requite the presence of post-exertional relapse and excludes patients with depressive of anxiety disorders. When these new criteria were applied, the authors found similar results with no significant differences in results results between the different criteria used.

Of note, after treatment 16% of patients in the APT group, 30% of patients in the CBT group, 28% of patients in the GET group, and 15% undergoing SMC were within ‘normal’ ranges for the fatigue and physical functioning outcomes measured. Let’s switch that around, 70% of patients in the CBT group and 72% of patients in the GET group had abnormal levels of fatigue and physical functioning. In addition, a clinically useful difference in results for the primary outcomes equated to 2 points on the Chalder fatigue questionnaire and 8 points for the short form 36 questionnaire, ie it just took a small change for the therapies to be clinically useful. Using these relatively loose criteria, only 42% of patients on APT, 59% of patients on CBT, 61% of patients on GET, and 45% of patients receiving standard medical care ‘improved’ at 52 weeks.

How were the results interpreted by the authors?

The researchers conclude that CBT and GET can be safely added to SMC to moderately improve outcomes for ME/CFS, and that APT is not an effective treatment. They also state that findings were similar for patients meeting the different diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS , and for those with depression. Importantly, they note that there were no important differences in safety outcomes between treatment groups

Author conclusions aside, how relevant are these results?

This study had many strengths including: (1) a low dropout rate in the study, which is impressive given that patients could drop out part way if they felt they no longer wanted to continue treatment; (2) there were high rates of patient satisfaction; (3) well defined treatment protocols were used to name but a few. However, there are several limitations of this study to consider:

- Patients who were unable to attend hospital were excluded, so the results from this study cannot really be applied to ME/CFS patients who are bed bound (there are quite a few out there)

- Standard medical care is not the same as the usual medical care given by a family doctor or GP

- Children who are also afflicted by ME/CFS were not included in the study

- Conventional criteria were used to define clinically useful differences between treatments

- Masking of patients or clinicians to the treatment given was not possible given the types of treatment given and research assessors were not masked, which may have led to reporting bias

One major objection to the study seems to be that the criteria used to select ME/CFS patients does not accurately reflect the ME patient (again see the response from Malcolm Hooper here). However, the authors do apply the results to alternative criteria for diagnosing CFS. Although this is no substitute for using the other ME/CFS criteria for inclusion into the study.

Perspective from Action for ME

Action for ME, a UK-based patient advocacy group have serious concerns about the PACE study, stating “The largest ever clinical trial into the effects of CBT, GET and adaptive pacing therapy (APT) has produced results that are clearly at serious variance from those reported by the largest ever survey of patient opinion on these forms of treatment.

We find the trial results extremely worrying because pacing, in the form that the MEA recommends, may as a result no longer be offered as a treatment option in NHS clinics. And at the same time, NICE may well strengthen its inflexible and unhelpful recommendations regarding CBT and GET.

We also fear that the way in which the results are already being reported in media headlines – eg Got ME? Just get out and exercise, say scientists – will lead some doctors to advise inappropriate exercise regimes that will cause a serious relapse.

This is not a good day for people with ME/CFS.

They have a complex multisystem illness that requires a range of treatment options based on their individual symptoms as well as the stage and severity of their illness”

So, there you go, Action for ME have a lot of serious concerns not only about the design of the study, but also the implications for ME/CFS patients throughout the UK.

Stop PACEing Around and Move On

The results from this study highlight the plight of patients with ME/CFS, and should fuel further research into the basic biology of what causes ME/CFS, together with clinical studies to determine what treatments really are effective for these patients. The lack of any harms with any of these treatments, should allay patient fears, that some of the treatments can do them harm. However, any confusion in findings can only be bolstered by rigorously designed clinical studies.

Tefalhead just hopes that something can be done to help his wife regain some type of ‘normality’ in her life, and is reminded that it isn’t just numbers reported in this study, but results from patients whose lives are hugely affected.

There is a great deal of disunity amongst ME/CFS patients, clinicians and patient groups, and it seems that the main people losing out here are the ME/CFS patients themselves. Tefalhead is at a loss as what to suggest in terms of a way forward… thoughts anyone? However, a line clearly needs to be drawn under the furore of the PACE study, and a fresh start made [Tefalhead suggests a group hug, but that may not be everybody’s idea of a good time].

Tefalhead has one last little grumble…headlines such as ‘Got ME? Just get out and exercise”. Are not only irresponsible but downright dangerous. Tefalhead spoke to a leading expert in the ME/CFS field at the weekend, who reiterated that any exercise therapy must be done under medical supervision. Scientific journalists- careful reporting PLEASE. If your headlines are taken literally by vulnerable patients, serious harm could be done.

Note from TefalHead: Your comments on this topic are appreciated, BUT please remember Tefalhead is as concerned with this issue as you are, and he is just trying to put the topic out there for debate. In other words… be nice, thanks. Oh, and Tefalhead has purposefully steered well clear from the XRMV issue, mainly to report the results of the PACE study and not distract from that. Tefalhead will review the XRMV story at some point in the future